I’m sure that you frequently find yourself wondering how you could better manage your time.

I’m no different and just like you probably have, I experimented with a few options.

Most of the options I tried are passive, they provide you with general principles or frameworks for allocating your time and dividing your workload.

One way or another, they show you how to better manage your energy levels.

However, I couldn’t find any method for active time management in emergency situations or when dealing with time creep.

This is why I will show you how you can use break-even analysis, adapted from financial management accounting, to improve your time management and put up a good fight in stressful situations.

Honorable mentions that almost do the job include the rule stating “if it takes less than X seconds, do it now. Else, do it later” or the Eisenhower matrix.

Now the bad news is that I couldn’t find any magic bullet because it’s hard to judge the effectiveness of a time management method other than by measuring some form of output.

The problem lies in both the “judging” part and the “output” part.

Time Management or Judgement?

Let me start with the output part.

For most of us, output is really a function of input (tasks, requests, workload etc.). That is the reason you work, study or pursue any other occupation.

Input is by nature uneven. Most things in nature come in waves, with troughs, peaks and periodicities.

In most jobs, you will have to deal with parallel tasks, increasing the complexity of time management.

If you’re lucky enough, you can rearrange these tasks to ensure you only deal with a sequential workload.

Still, no matter how good you are at managing time, you will find yourself overwhelmed at some point (that is a good sign of your job not being redundant). Peaks are to be expected.

That doesn’t mean your time management sucks. It’s just how reality works.

As for the “judging” part, it’s linked to the hedonic treadmill.

As your time management improves (along with your productivity), your expectations for what (peak) performance should look like also increase.

Unfortunately, time management can only go so far before technology or recruiting have to be introduced in the picture to sustain output growth.

Getting to the (break-even) point

You might be wondering at this point how this article will help you in your quest for efficient time management?

We will draw from an economic concept taught in all business schools: break-even analysis.

The idea is that, instead of dwelling on the details of each possible scenario of sales to forecast revenue and then deduce profits at the end, you determine how many units of sales you will need to “break-even”.

This target number of sales is called the break-even point.

It’s not complex but there could be more rigorous ways to define it in economics.

But that is beyond the point of this article. My goal is to draw a parallel between break-even analysis and time management.

As I cannot assume everyone went to business school or were exposed to this specific concept, I will give you a refresher on break-even point calculation.

We will consider the case of Mr. Yogurt who’s thinking about launching a yogurt business.

You start with a lump sum investment to launch any business. For simplification, this investment will be considered an expense in full.

These expenses are fixed. This means that they can reasonably be expected to stay constant as the level of production varies.

An example is rent. Even if you produce 10 extra units of yogurt, you won’t have to rent extra space for production or storage. We can therefore say that rent is (relatively) fixed.

What will change however is that each of these new units of yogurt will require individual packaging, that will have to be bought or manufactured.

This is a variable kind of expense as it changes proportionally to the change in the level of output.

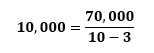

We will go further and only concern ourselves with the unit variable cost (conveniently set at $3).

Each new unit of yogurt costs $3 to manufacture.

Mr. Yogurt just informed me that fixed expenses are set at a nice round $70,000 thanks to his exceptional business acumen.

Assuming there is demand for these yogurts (who buys those orange and chocolate chip ones?), a fair price of say $10 can be fetched for each new unit.

We’ll assume that this price is a constant (a *perfect* assumption to make, especially considering you probably already assumed at some point movement without friction for physics class).

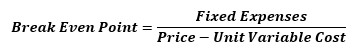

The break-even point can finally be introduced. I reckon it’s just a very fancy term for this formula:

Whew, took us long enough to get here but the fun stuff starts now.

The denominator (Price – Unit Variable cost) is called the Unit Contribution Margin (UCM).

Again, fancy lingo to describe how much money each new unit of yogurt brings in.

It cannot yet be called profit since we still have the fixed expenses to account for.

The break-even is the solution to how many “UCMs” it takes to cover all the fixed expenses.

It will take 10,000 units of sales for Mr. Yogurt to cover all his expenses and hopefully start making a profit.

Props to you if you still remember the topic of this article. I did go on a massive tangent but bear with me as we finally enter the conclusion of this analogy. You will see that everything fits nicely.

Hypotheses For Our Analogy

In the good and services market, we exchange units of consumption for monetary units.

Simply speaking, you might engage as a consumer of consumption units or as a hoarder of monetary units.

The point can be made that you exchange monetary units for other monetary units. This is the case if we consider the physical aspect of the exchange as a mere medium (labor hours for goods and services).

Similarly, in your time management journey, you exchange units of time for other units of time with the goal of spending the least amount of time for a given “physical” output.

Your work hours are (relatively) fixed but they are not really the fixed expenses in our break-even model.

Break-even analysis applied to time management is a bit more subtle and that is what makes it so useful and versatile.

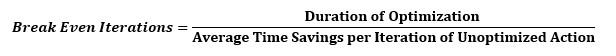

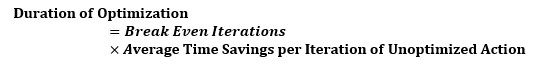

It’s not a checklist but rather a generalized powerful principle as the formula shows:

Fixed expenses have now become the time you spend on the optimization of the current task (sharpening your proverbial axe). This is our initial investment in units of time.

The expected time saved on each iteration is our UCM (Unit Contribution Margin). It represents the time you save on each move to cut down the tree after sharpening our proverbial axe.

It’s the difference between the old duration (our Unit Variable Cost) and the new optimized duration it takes to perform the task (our Price).

The break-even result you obtain can be interpreted as the minimum number of times you should be currently performing the task for the optimization to be justified and add value.

Time is Monetary Units

Unlike in our simplistic break-even model for production, we are not limited to one scenario where fixed expenses are set to a certain value.

You can flip the formula like this:

You can come up with different actions to take that could yield different expected time savings and decide which one to pursue depending on how much free time you have to carry the optimization.

The best absolute improvement would make sense over the long run, but it might not be the appropriate choice when you have to deliver results in 15 minutes.

This sounds so obvious that you might wonder whether this is just plain over-complexification, opposite in essence to time management.

The same argument could be made for the teaching of the break-even method in b-schools.

A true breakthrough is not about how complex the jargon sounds but about the change in perspective it brings about in you.

The simple transition to an analytical paradigm for time management expands your toolbox with a tool that is simple enough not to require multiple moving parts (increase cognitive load).

This also makes it robust enough to be used reliably in time-constrained stressful situations where people tend not to perform at their best (props to you if you do).

In more practical terms, one of the ways I use the break-even formula on the go is to follow this process:

- Notice a task is not optimized as much as it could be (possible improvement of (x) units of time);

- Brainstorm solution (i) that does fits the same requirements as current unoptimized task;

- See how much time solution (i) would require to implement (Ti);

- Divide (Ti) by (x) to obtain N (the number of times I should currently be performing the unoptimized task for the new task to make sense);

- Reject or implement optimization action depending on the break-even point N and my current “sales” (the number of times I perform the current unoptimized task);

- Rinse and repeat.

One important note is that the optimization action doesn’t necessarily have to be a onetime action occurring during the timeframe of optimization (a workday for example).

It can also take the form of a series of tasks with periodicity even exceeding that of the previous unoptimized task). It’s about the total volume of work (time*frequency).

Conclusion

As with any (conceptual) tool, you get better at using it and it becomes more useful in the process.

It allows you to proceed in a rational justified course of action rather than rely on instinctive hunches that often require past experience and thus are quite unreliable when it comes to new situations and aggressive deadlines.

Those situations are coincidentally what usually sparks last-minute stressful episodes (in my personal experience).

I hope this article helped you or at least ignited an interest in you for better time management.

Thank you for reading and expect more quality content (with hopefully less unrequested humor).

Love the concept ,will definitely keep it in mind next time I have a tight deadline. Thanks for sharing!

Glad to hear that Ahmad